My wife and I recently watched Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin., a movie that I would recommend. An alternate title could have been, Dietrich Bonhoeffer Changes His Theology about Nonresistance.

Along those lines, I’ve got some food for thought for those who believe that the early church universally held to an Anabaptist view of nonresistance—the idea Christians should never physically do anything to defend themselves or others (the latter of which many of us consider to be a transgression of the commandment to love our neighbors as ourselves).

Modern Anabaptists often cite the writings of early church fathers to buttress their beliefs and practices, claiming that those writings must surely reflect the views that the original apostles held but did not express in the New Testament epistles. I don’t agree with that logic, but for the sake of this article, let us assume it is correct.

We know that Clement of Rome is one of the most ancient of the “Apostolic Fathers” (the earliest Christian theologians who may have had personal contact with the original twelve apostles). Clement is mentioned by Irenaeus and Tertullian as Bishop of Rome. His epistle, 1 Clement—usually dated around AD 96—is considered to be one of the earliest writings, if not the earliest writing, of all the Apostolic Fathers. He wrote primarily to admonish the Christians in Corinth (to whom Paul earlier wrote) to love one another. In 1 Clement 55:2-3, Clement wrote of some inspiring examples of love:

We know that many among ourselves have delivered themselves to bondage, that they might ransom others. Many have sold themselves to slavery, and receiving the price paid for themselves have fed others. Many women being strengthened through the grace of God have performed many manly deeds (emphasis mine).

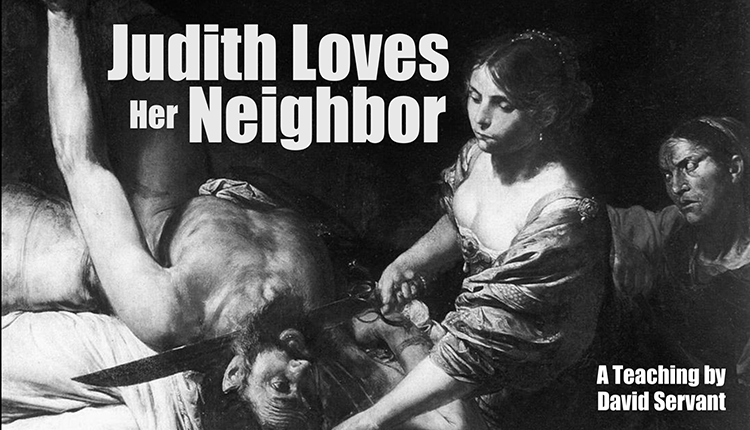

Clement then immediately cited an example of one particular women’s act of love, a woman with whom all of his contemporary readers would have been familiar. Her name was Judith, and she is the central figure in the Book of Judith that we find in every Catholic Bible, in the Protestant Apocrypha, and in the Septuagint. Judith was one who, in Clement’s words, was “strengthened through the grace of God” to “perform a manly deed.” That is, God supernaturally helped her to do something not usually done by women. And what great love did Judith display that Clement wants his readers to recall in order to be inspired by it? Here it is, in Clement’s own words:

The blessed Judith, when the city was beleaguered, asked of the elders that she might be suffered to go forth into the camp of the aliens. So she exposed herself to peril and went forth for love of her country and of her people which were beleaguered; and the Lord delivered Holophernes into the hand of a woman (1 Clement 55:4-5, emphasis mine).

All of Clement’s contemporary readers knew Judith’s story in much more detail. Judith, a beautiful widow, unselfishly risked her life on behalf of her countrymen whom she loved, going out of her besieged city to win the trust of the enemy Assyrian general, Holophernes, whom she personally decapitated after getting him intoxicated. (You go, girl!) She then carried his head back to her fearful countrymen, and the Assyrians, having lost their leader, dispersed. Israel was saved. (For more details, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judith_beheading_Holofernes).

This kind of “non-non-resistant” teaching about love by Clement—a major, respected Christian leader—doesn’t surprise those who know the Bible, as we can read many stories of God’s people, who by faith, “conquered kingdoms…from weakness were made strong…became mighty in war…put foreign armies to flight,” all heroes of faith mentioned in Hebrews 11 (in the New Testament by the way), people like Judith who were motivated by their love for God and neighbor to physically resist evil.

So how does that passage in 1 Clement harmonize with the Anabaptist interpretation of Matthew 5:39 and the common Anabaptist claim that all the church fathers universally agree with the Anabaptist view of nonresistance? It doesn’t.

Interestingly, in that same passage, Clement also mentions Esther, another brave woman of great love who delivered the nation of Israel from slaughter. Clement calls her “perfect in faith.”

The story of Esther is not a story about someone (Esther) or a group of people (Israel) who let themselves and their neighbors be slaughtered, as Anabaptists say we should all do when faced with danger upon our lives or the lives of others whom we love.

I’ll leave readers to ponder on their own how to harmonize Matthew 5:39 with the rest of the Bible and their God-given consciences. It isn’t that difficult. But who can argue with the words often attributed to Bonhoeffer: “Not to act is to act”?